Bitter Legacy of India’s Partition – Article on Culture Archive

Uncover the bitter legacy of India’s Partition. From British-drawn borders to mass killings and forced migrations, this article delves into the tragic consequences of Partition, a wound that still bleeds today.

In August 1947, India gained independence after 200 years of British rule. What followed was one of the largest and bloodiest forced migrations in history. An estimated one million people lost their lives. Before British colonization, the Indian subcontinent was a patchwork of regional kingdoms known as princely states populated by Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, Parsis, and Jews. Each princely state had its own traditions, caste backgrounds, and leadership. Starting in the 1500s, a series of European powers colonized India with coastal trading settlements.

By the mid-18th century, the English East India Company emerged as the primary colonial power in India. The British ruled some provinces directly and ruled the princely states indirectly. Under indirect rule, the princely states remained sovereign but made political and financial concessions to the British. In the 19th century, the British began to categorize Indians by religious identity—a gross simplification of the communities in India. They counted Hindus as “majorities” and all other religious communities as distinct “minorities,” with Muslims being the largest minority. Sikhs were considered part of the Hindu community by everyone but themselves. In elections, people could only vote for candidates of their own religious identification.

These practices exaggerated differences, sowing distrust between communities that had previously co-existed. The 20th century began with decades of anti-colonial movements, where Indians fought for independence from Britain. In the aftermath of World War II, under enormous financial strain from the war, Britain finally caved. Indian political leaders had differing views on what an independent India should look like. Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru represented the Hindu majority and wanted one united India. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who led the Muslim minority, thought the rifts created by colonization were too deep to repair. Jinnah argued for a two-nation division where Muslims would have a homeland called Pakistan.

Following riots in 1946 and 1947, the British expedited their retreat, planning Indian independence behind closed doors. In June 1947, the British viceroy announced that India would gain independence by August and be partitioned into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan—but gave little explanation of how exactly this would happen. Using outdated maps, inaccurate census numbers, and minimal knowledge of the land, in a mere five weeks, the Boundary Committee drew a border dividing three provinces under direct British rule: Bengal, Punjab, and Assam.

The border took into account where Hindus and Muslims were majorities, but also factors like location and population percentages. So if a Hindu majority area bordered another Hindu majority area, it would be included in India—but if a Hindu majority area bordered Muslim majority areas, it might become part of Pakistan. Princely states on the border had to choose which of the new nations to join, losing their sovereignty in the process. While the Boundary Committee worked on the new map, Hindus and Muslims began moving to areas where they thought they’d be a part of the religious majority—but they couldn’t be sure. Families divided themselves. Fearing sexual violence, parents sent young daughters and wives to regions they perceived to be safe.

The new map wasn’t revealed until August 17, 1947—two days after independence.

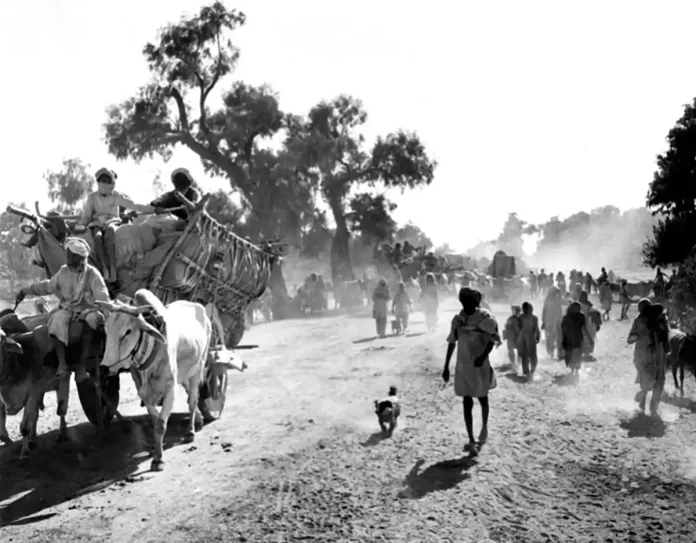

The provinces of Punjab and Bengal became the geographically separated East and West Pakistan. The rest became Hindu-majority India. In a period of two years, millions of Hindus and Sikhs living in Pakistan left for India, while Muslims living in India fled villages where their families had lived for centuries. The cities of Lahore, Delhi, Calcutta, Dhaka, and Karachi emptied of old residents and filled with refugees. In the power vacuum British forces left behind, radicalized militias and local groups massacred migrants. Much of the violence occurred in Punjab, and women bore the brunt of it, suffering rape and mutilation.

Around 100,000 women were kidnapped and forced to marry their captors. The problems created by Partition went far beyond this immediate deadly aftermath. Many families who made temporary moves became permanently displaced, and borders continue to be disputed. In 1971, East Pakistan seceded and became the new country of Bangladesh. Meanwhile, the Hindu ruler of Kashmir decided to join India—a decision that was to be finalized by a public referendum of the majority Muslim population. That referendum still hasn’t happened as of 2020, and India and Pakistan have been warring over Kashmir since 1947. More than 70 years later, the legacies of the Partition remain clear in the subcontinent: in its new political formations and in the memories of divided families.

Credit: Commons wikimedia

Check out our latest blog on – Stories behind Independence Day, You Never Knew – Click here to read