Chandrayaan 3 Finds Molten Rock: Scientific Research on Space Technology

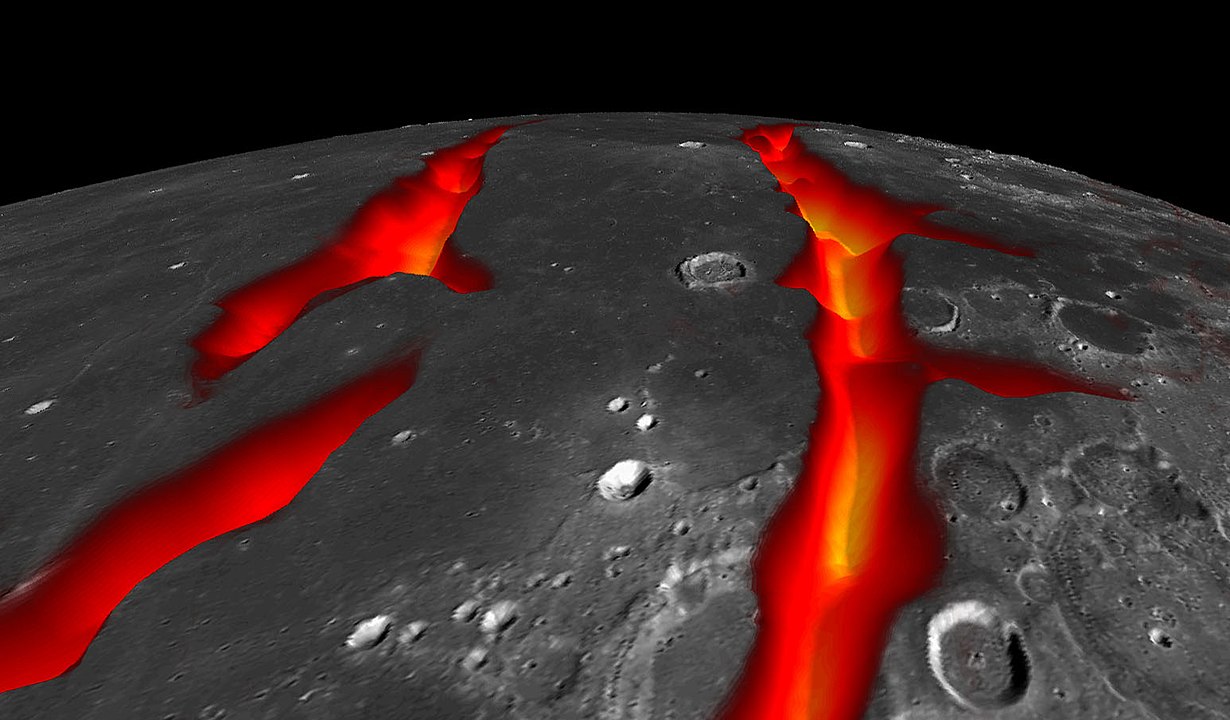

The new evidence from the Chandrayaan 3 expedition in India has provided strong support for the hypothesis that there was a time when the moon was completely covered with a huge ocean of molten rock. These are published in Nature, and they give insight into geological past events on the moon thereby changing its formation history.

On August 23rd, 2023 Vikram Lander made history by successfully touching down on the Moon’s surface. In addition to this success, the Pragyan rover deployed off Vikram and went further south than any other spacecraft ever landed to date.

Consequently, scientists were given an unprecedented chance to examine features on the lunar surface hence helping establish certain facts concerning these geological aspects of the Moon. The study provided the latest information on space science.

Insights from the South Pole

The Chandrayaan-3 mission’s landing site offered a unique opportunity to study the lunar south pole’s regolith, or surface soil. Pragyan rover measurements showed that this regolith has a high level of chemical similarity; it is mainly composed of ferroan anorthosite, a white rock.

The new scientific research on space technology is important. When compared with samples from the Moon’s equatorial region collected during the Apollo 16 expedition and the Soviet Luna-20 mission in 1972, uniformity in the chemical composition of samples from this southern region suggests that these regions may share a common geological history.

Despite being located far apart from each other, their similarity in terms of chemicals supports strongly one hypothesis: once upon a time the moon had just one giant ocean which was filled with molten rock.

The Birth of the Moon and its Magma Ocean

The Moon is believed to have been created as a result of a huge impact between Earth and a Mars-sized object. This collision caused a large amount of material to be thrown into space which ultimately came together to form the Moon. In the early stages, it appears that the moon was completely covered by a magma ocean that lasted for tens or even hundreds of millions of years.

Eventually, this molten ocean cooled down and solidified giving rise to ferroan anorthosite rocks which now make up much of the lunar crust. The recent Chandrayaan-3 findings bolster the theory that these ancient rocks represent remnants of the first lunar crust where lighter minerals floated up while denser ones sank deep into forming the moon’s mantle.

Orbital Measurements and Lunar Meteorites

The implications of this research extend far beyond the moon’s surface. Chandrayaan-3’s data align well with measurements collected during previous India’s moon missions, specifically Chandrayaan-1 and Chandrayaan-2, which confirms a significant likeness in the materials on the Moon’s surface over substantial distances.

This uniformity strengthens trust in orbital datasets that indicate that the lunar surface within this area has nearly identical chemical composition for several kilometres.

Additionally, these “ground truth” measurements are vital for constraining lunar meteorite interpretations. There are some rock pieces thrown into space by impacts from celestial bodies that fall to Earth after their trajectory intersects with our planet while others do not reach far before they disintegrate.

These fragments provide important insights as they come from regions of the moon not yet explored by astronauts. However, because it is difficult to determine the origins of these meteorites, results collected by Chandrayaan-3 will help scientists place them in context so as to understand better moon geology.

A New Chapter in Lunar Exploration

The concept of the lunar magma ocean is traced to the return samples from the Apollo 11 mission that landed within an area composed mainly of dark basaltic rocks. Nonetheless, white rock fragments rich in the mineral anorthite were also found in the Apollo 11 soils which led scientists to suggest that there could be an ancient lunar crust composed of ferroan anorthosite.

Since then, more complex models have been developed by scientists who are attempting to reason out the history of the geological earth’s moon. This implies that the lunar crust may contain several layers with ferroan anorthosite at its top and other rocks below it being richer in magnesium. Curiously, Chandrayaan-3 measurements reveal a higher proportion of magnesium than expected suggesting a complex and stratified structure inside the lunar crust.