Napoleon’s Waterloo Defeat – Blog on Culture & Social History

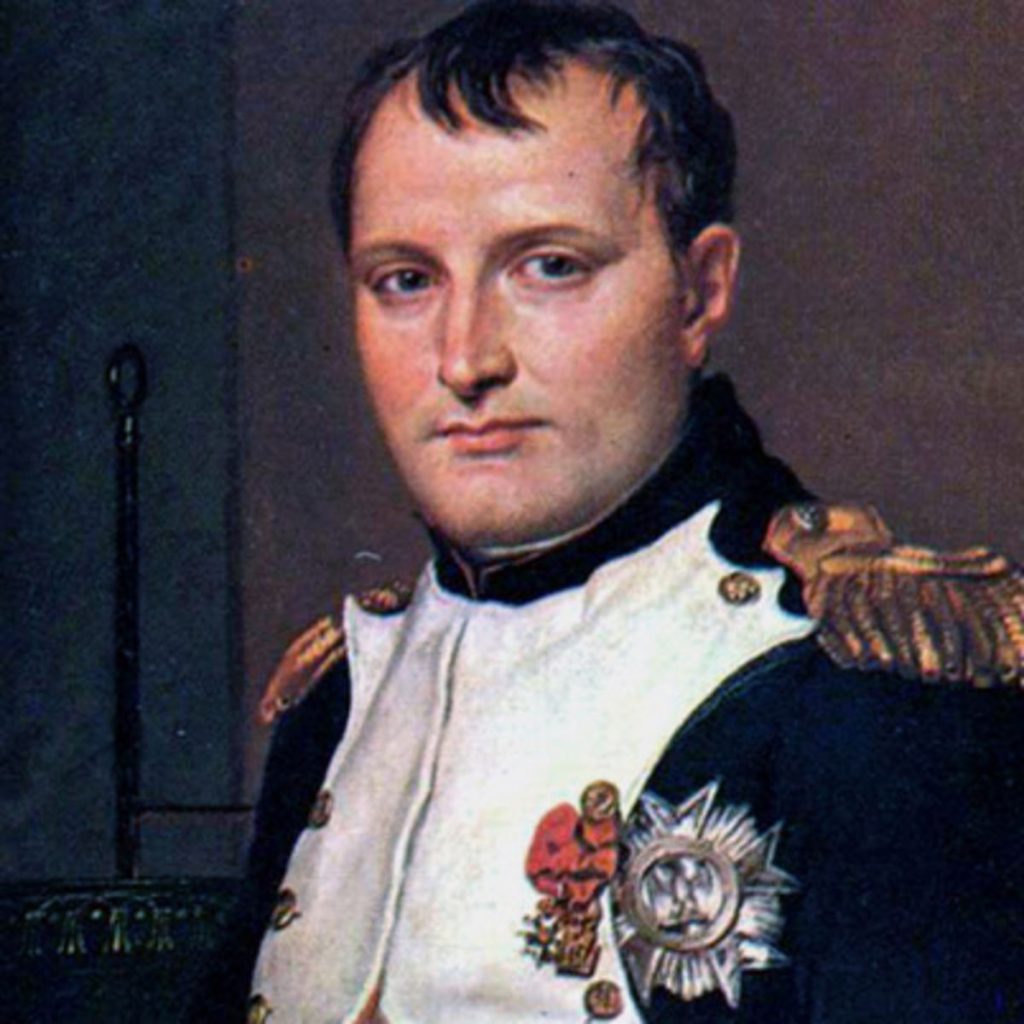

April 1814. For ten years, one man has dominated Europe: Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the French. Under his military genius, France conquered an empire that spanned the continent. But finally, he has been defeated by a grand coalition of his enemies.

Napoleon is forced to abdicate and is exiled to the tiny island of Elba, while the Bourbon monarchy is restored to France in the corpulent form of Louis XVIII. But rumours soon reach Napoleon that France would welcome his return. The French people have little love for the monarchy or its hangers-on, the very people whose excesses led to the French Revolution 25 years before. He also learns that at the Congress of Vienna, his enemies are locked in bitter dispute over the future of Europe.

Napoleon decides to act. After just ten months in exile, he returns to France, where the troops sent to arrest him rally to his cause instead. Most of France soon follows suit. But in Vienna, the Coalition immediately puts their differences to one side. They declare Napoleon an outlaw and mobilise their forces for war. Napoleon knows he must act boldly before the Coalition launches a co-ordinated invasion of France. He counts on winning a quick victory and then negotiating peace from a position of strength.

He targets the Coalition armies within easiest reach: Prince Blücher’s Prussian army and the Duke of Wellington’s Anglo-Allied army, both camped in Belgium. Napoleon’s force is a match for either Coalition army on its own, but he’ll be heavily outnumbered if they’re able to join forces. So he must keep them apart and defeat each in turn. Napoleon’s army crosses the frontier near Charleroi, intending to drive a wedge between the two Coalition armies. The next day, Napoleon sends his Left Wing under Marshal Ney to take the crossroads at Quatre Bras.

There Ney clashes with Wellington’s army, still scrambling into position. The Allied troops fight off a series of French attacks and just manage to hold their ground. The same day, Napoleon attacks Blucher’s Prussian army with his main force near the village of Ligny. The battle is a brutal slugging match, but the French emerge triumphant. The 72-year-old Blucher leads a cavalry charge in person and has his horse killed under him. He only just escapes capture.

The Prussian army retreats, but it is not broken. Napoleon sends his Right Wing under Marshal Grouchy to keep them on the run and turns his own attention to Wellington’s army. The British general doesn’t receive news of Blucher’s defeat until the next morning, at which point he orders a retreat through heavy summer showers to a position 8 miles south of Brussels, near the village of Waterloo. There, he receives a promise from Blucher that the Prussians will march to his aid the next morning, so Wellington decides to stand and fight. Wellington has chosen his battlefield with care.

His troops are behind a gentle ridge, which will give them some shelter from French cannon fire. His right flank is anchored on the farmhouse of Hougoumont, his centre on the farm of La Haye Sainte, and his left on the farm of Papelotte. All three are fortified and garrisoned with elite troops. Wellington’s men need every advantage they can get. The opposing armies are roughly equal in size, but his is a ragtag mix of British, Dutch, and German troops, many of whom have never seen combat before. They will have to hold off Napoleon’s army of veterans until Prussian reinforcements arrive, or the battle and probably the war will be lost. Sunday dawns bright and fair.

Napoleon has ordered Marshal Grouchy to pursue the Prussians and keep them busy while he defeats Wellington’s army at Waterloo and opens the road to Brussels. But it’s Grouchy who gets pinned down, fighting the Prussian rearguard at Wavre. The main Prussian force eludes him and is already marching to Wellington’s aid. At Waterloo, Napoleon delays his attack, waiting for the ground to dry, which will make movement easier for his troops. But the lost hours will later prove costly. The battle begins around 11 am when Napoleon orders a feint against Wellington’s right flank at Hougoumont. He hopes Wellington will commit his reserves here, drawing them away from the centre where the main blow will fall. But Hougoumont’s British and German defenders hold their ground.

Defenders cling on desperately throughout the day. At one point, the French force their way through the main gate, but it is shut behind them and the intruders are all killed. Wellington later calls it the decisive moment of the battle.Around noon, 80 French cannons open fire against the main Allied line. Most of Wellington’s men are out of sight on the reverse slope, but many cannonballs still find their mark, smashing bloody holes in the Allied ranks.

At 1:30 pm, Napoleon sends in his infantry. The French columns are met by disciplined musket fire and then charged by British heavy cavalry.The French attack disintegrates as Napoleon’s men try to save themselves from the crushing hooves and flashing sabers. Scores of Frenchmen are ridden down, and two of their famous Eagle standards are captured.But the British cavalry, exhilarated by success, charge too far. They become scattered, their horses blown. At their most vulnerable, they are counter-charged by French cavalry and suffer terrible losses. Among the dead is Major General Sir William Ponsonby, commander of the Union Brigade.

Around 4 pm, Marshal Ney thinks he sees the Allies begin to retreat and leads a mass cavalry charge to drive home the advantage. But Ney is wrong. The Allied infantry are still holding their ground.Ready, formed in hollow squares with bayonets fixed. The French cavalry can’t break into these impregnable formations; they can only circle impotently until they retreat or are shot from the saddle. Ney’s failure to support this attack with either infantry or artillery is a serious blunder.

Meanwhile, Blucher’s Prussians have begun to arrive. They capture the village of Plancenoit, threatening Napoleon’s flank and forcing him to send reserves to recapture it. Around 6pm, French infantry finally capture the farmhouse of La Haye Sainte in the center of the battlefield. It allows the French to bring forward artillery and blast the Allied squares from close range. They can’t miss the closely packed formations, and casualties quickly mount. It begins to seem that if Wellington’s army doesn’t retreat, it will be killed where it stands.

But the situation for Napoleon is also desperate. The Prussians are arriving in force, and he’s running out of men to throw against Wellington’s army. So he turns to his ultimate reserve, the elite Imperial Guard, the most feared troops in Europe.At 7.30pm, 3,000 of these battle-hardened veterans march past their Emperor and across the corpse-strewn battlefield towards the Allied center. Wellington’s redcoats rise to meet them and pour devastating volleys of musket fire into their ranks. When the Allies fix bayonets and prepare to charge, the Imperial Guard wavers and then retreats.

Wellington, sensing victory, orders a general advance. About the same time, the Prussians recapture Plancenoit. News of the Imperial Guard’s defeat and rumors of encirclement by the Prussians sweep through the French ranks. Panic breaks out, and the French army flees the battlefield.

Only Napoleon’s Old Guard maintain their discipline, mounting a heroic but doomed rearguard action. Napoleon himself is forced to abandon his carriage and barely escapes the pursuing Prussian cavalry. The battle is won. The Duke of Wellington and Prince Blucher meet and congratulate each other outside Napoleon’s former headquarters, an inn called La Belle Alliance. Blucher thinks it’s the perfect name for their shared victory, but Wellington prefers the more English-sounding ‘Waterloo’, where he has his own headquarters.

The Battle of Waterloo was, in the words of the Duke of Wellington, ‘a damned near run thing’. It was also one of the bloodiest battles of the age. Around 50,000 men were killed or wounded: 23,000 Coalition casualties, 27,000 French. Due to an appalling shortage of medical care, many of the wounded were left lying on the battlefield for several days.

Napoleon was utterly defeated. Unable to raise another army, he surrendered to the British. They transported him to a second exile, on the tiny, remote Atlantic island of Saint Helena. This time there was no escape. He died there six years later.Waterloo marked the beginning of a period of relative peace in Europe—there were no wars between the great powers for 40 years. And the British would not fight on the Continent for another hundred years, until the summer of 1914.

Forty years after the battle, a pioneer in the new art of photography captured these remarkable images. They are veterans of Napoleon’s armies, by then all old men in their seventies and eighties. Among them, Sergeant Tania of the Imperial Guard, Moret of the 2nd Regiment of Hussars, and Verline of the 2nd Guard Lancers. These faces are a tantalizing link to the dramatic events that shaped the course of history two centuries ago.

To read more blogs on culture and social history – click here